The Mega-Void - Unleashing the Communicative Impact of Tall Buildings

Patrik Schumacher, Zaha Hadid Architects, London 2020

Published in: AD (Architectural Design) 05/Vol 90/2020: IMPACT, edited by Ai Rahim & Hina Jamelle

The digital design tools that became available to our discipline since the 1990s were congenial to our concurrent pursuit of complexity and empowered radically new concepts and sensibilities that ushered in the movement and style of parametricism. Twenty-five years later we are impacting at scale, across all project types. The high-rise typology was the most resistant and last to open up to the impact of the new complexity and dynamism demanded and delivered by the digital revolution.

Fig.1 Zaha Hadid Architects, Leeza Soho Tower, Beijing 2019

Parametricism has matured and is delivering sophisticated state of the art products at scale. This tower offers collaborative office space for hundreds small and medium enterprises gathered around the world’s tallest atrium.

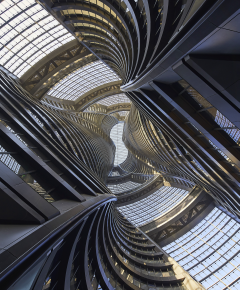

Fig.2 Zaha Hadid Architects, Leeza Soho Tower, Beijing 2019

The Mega-void cuts right through the tower in a continuous spiralling move that opens the tower to its urban context. The smooth trajectory of the void is punctuated by by big trusses that stich the two slices together.

Historical Context, Task and Opportunity

We are living in an era of unprecedented urban concentration. Contemporary urban life is becoming ever more complex, with divers, overlapping audiences, browsing through many simultaneous urban amenities. A dense proximity of complementary social offerings, and a new intensity of communication across different activities distinguishes contemporary life from the modern period of separation and repetition. Such a network of activities can evolve bottom up in an urban texture that offers the spatial connective freedom of urban channels and voids. What would it take to continue such an evolving synergetic urbanity within a building?

The skyscraper seems locked in the bygone fordist paradigm of segregating segmentation and serial repetition. The tower typology is the last bastion of this bygone era, and has so far resisted the injection of any significant measure of spatial complexity. Towers are still driven by pure quantity. Their volume is generally generated by pure extrusion and their inner space is nothing but the multiplication of identical floor-plates. They are vertical dead end corridors, usually cut off from the ground-plane by a podium. All this is like this for seemingly good economic reasons. However, this economy, an economy of costs rather than benefits, is increasingly dubious.

The sky-scraper’s organizational structure is too simple and too constricting. Towers are hermetic units, which are themselves arrays of equally hermetic units (floors). This feature of strict segmentation with its characteristic poverty of connectivity is antithetical to contemporary work patterns and business relations as well as to contemporary urban life in general. The time is ripe to challenge the standard tower typology and demand that it too participates in the general societal restructuring from Fordism to Postfordism.

Postfordist Costs and Benefits

The usual tower typology stacks up floors that remain blind to each other. Due to the usually centrally located core, the usable surfaces on each floor are also highly segregated. Towers are usually big investments and economic pressures are brought to bear demanding cost efficiency. But costs are only one side of an economic appraisal. A proper appraisal includes both costs and benefits in a cost-benefit analysis. The problem is that the benefit of providing floor surface is obvious and its measurement is trivial, while the appraisal of the benefits of navigability, inter-visibility and inter-awareness afforded by voids is not so trivial, cannot be as easily measured, and might therefore be overlooked. What is required here is entrepreneurial market leadership based on the intuition that the intuitive appeal of spaces with superb visual connectivity will draw in clients who are willing to pay the extra costs and more.

The idea could not be simpler: All buildings, especially towers, must become to a large extent empty, hollow, i.e. we must substitute usable floor surface with voids affording deeply penetrating internal vistas.

The author has confidence that this will succeed within our contemporary knowledge economy with creative industry firms. Here real estate costs are only a small fraction of human capital costs, and the prospect of increasing creative knowledge worker productivity will be very much worthwhile the expense of cutting voids into the dense packing of floors and desks. Visual density is more important than physical density, because it facilitates density of communication. This is not only a matter of facilitating actual encounters, conversations, exchanges and collaborations but works already via the thrill and stimulation of being viscerally immersed within a cluster of creatives. This sense of stimulation has its own intuitive rationalty: the prospect of encounters, of learning opportunities, of collaborative ventures - all productivity and thus life enhancing - attracts those of us eager to thrive professionally.

What is the point of agglomerating thousands of people within a headquarters tower, if not the facilitation of cooperation, planned and unplanned? Postfordism implies that workers are no longer chained rigidly into an assembly line. Production is automated via reprogrammable robotic systems. This new technological era ushered in by the combustive combination of computation and networking, and now further enhanced via AI, has an enormously expanded capacity to absorb innovations. Production robots can be re-programmed just in time and new service apps uploaded to billions at all times. The same applies to software updates. The Fordist mechanical assembly lines had very little ability to take on product innovations on the fly. Here cycles of innovation were counted in years or decades rather than months and weeks. In any case, the workers were still locked into the assembly chain as well. In contrast, all work is now able to focus on continuous innovation: R&D, marketing, financing. As workers become creative knowledge workers they must become self-directed nodes in a continuous process of network self-organisation. There is no way that this can be planned from above. The leadership is busy building open platforms that might allow this self-organisation to flourish. Buildings are one important type of platform that can make a difference. The costs of creating or renting these spatial communication platforms dwarf in comparison to the costs of the human capital that fills these buildings. A building that wastes and stunts this human capital is damaging the economy, irrespective of its own construction costs. All the ideas, innovations and productive collaborations that might have been the result of bringing thousands of smart people into a volume, are the invisible opportunity costs that are missing from the calculations of each project budget. However, comparative analyses on the urban scale have demonstrated what urban economists call agglomeration economies.

Interior Urbanism and Unleashed Navigation

The idea of explicitly introducing navigation as a key agenda to be considered in the design of towers goes hand in hand with the attempt to inject a certain measure of differentiation and complexity into the vertical trajectory of the tower. The repetition of the same does not require a special design effort to facilitate orientation. And usually the navigation of towers is dead simple: just step into the elevator and select the required floor. As the complexity of the tower increases and public functions start to penetrate the tower, navigation becomes an issue. Navigation means much more than mere mechanical circulation. Navigation is the perceptual and conceptual penetration of a deep space. A legibly configured navigation space is called for that affords a certain visual penetration and mental map. Floors are no longer segregated black boxes. Such a space invites roaming rather than merely the seeking out of a pre-planned, known destination. While maintaining a strong sense of orientation, a strategic browsing should be made possible, affording unplanned but non-random encounters, just like in a buzzing city fabric. This is the idea of ‘interior urbanism’. The question is: Can the idea of interior urbanism be applied to towers? One solution is the idea of the mega-atrium, the tower as continuous void that can bring thousands of potentially inter-relevant activities into mutual view. An example of this is Zaha Hadid Architects’ headquarters design for the Tai Kang Conglomerate in Wuhan.

Fig.3 ZHA, Mega-Atrium, Tai Kang Headquarters, Wuhan 2016-2022

This massive void gathers the many firms of the conglomerate, plus retail spaces and a small business hotel. This is a 21st Century city square, a truly urban interior.

Fig.4 ZHA, Mega-Atrium, Tai Kang Headquarters, Wuhan 2016-2022

The dramatic spectacle of this interior urbanism delivers a thrilling sensation. But this sensation makes productive sense. The visceral attraction is signalling the anticipated richness of productive encounters.

These spaces express and facilitate the complexity, dynamism and communicative intensification of urban life in our 21st Century Network Society. Buildings must become porous and urbanised on the inside, allowing for increasing inter-visibility between the diverse social activities brought together, to maximize co-location synergies and to facilitate a browsing navigation. Another example of this is Zaha Hadid Architects’ Dominion Tower in Moscow (see below) where a synergy cluster of creative industry firms have naturally found each other.

Fig.5 ZHA, Atrium, Dominion Tower, Moscow 2015

This office tower in Moscow became a cluster of related creative industry firms who all guessed right that this space would attract like-minded firms. Natural light, inter-visibility and shared social spaces create a fertile networking hub.

The motivation to move into cities, ever larger, ever denser cities, and into ever larger buildings, is clear: we come together to network, to synergize knowledge, to exchange and to cooperate. The built environment becomes an information-rich, empowering and exhiliarating 360 degree interface of communication and networking machine. However, it thereby also becomes an experience machine. Lose yourself and discover yourself!

The taller the tower, the more important becomes its mode of interfacing with the ground-plane. The large amount of traffic coming down from the tower usually occasions special spatial provisions on the ground floor. For instance, in the case of a hotel tower all additional facilities like lobbies, restaurants, bars, retail etc. are located on the ground floor or near to the ground. Tall residential towers, as well as office towers, also demand ground-level expansion. Usually these additional space-requirements are catered for by means of discrete podium blocks that separate the shaft of the tower from the ground. One of our key ambitions has been to find convincing alternatives to the ‘tower on podium’ typology, alternatives that avoid the intervention of a discrete third element between the ground-surface and the tower itself. One such strategy is the sunken retail podium, as executed in ZHA’s Leeza Tower in Beijing.

The agendas of differentiation, interface and navigation combine to articulate a new paradigm for the design of complex towers in urban contexts. On this new basis the tower typology will receive a new lease of life in the central metropolitan societies, where the desire for connectivity (rather than pure quantity) drives urban density. In the future, even more than is evident already now, this super-dense build up will be a mixed-use build up, where multiple life-processes intersect. These life-processes need to be ordered in intricate ways that nevertheless remain legible. More than ever, the task of architectural design will be about the transparent articulation of relations for the sake of orientation and communication. Differentiation, interfacing and navigation are joined in a clear agenda that will require a sophisticated, versatile language of architecture. An expressed contemporary structure, like an optimized exo-skeleton, helps naturally to differentiate the tower along its vertical axis. The exo-skeleton also takes pressure off the core and allows more freedom for interior voiding. The voids which are strung along the vertical axis might fuse into a mega-atrium that also affords panoramic elevators to fly through a navigation space that functions like a vertical urban street. An example for this is Zaha Hadid Architects’ Morpheus tower in Macao.

Fig.6 ZHA, Atrium, Morpheus, Macao 2019

Morpheus sports an exo-skeleton that gives ample freedom to the complex void unfolding inside. This vertiginous space of flying can be traversed via 180 degree glazed panoramic elevators. The void is traversed by bridges that host social spaces like cafés and restaurants. Vistas open out also into the urban context.

Breaking the Mold: The Leeza SOHO Tower

Located on Lize Road in southwest Beijing, the Leeza SOHO tower anchors the new Fengtai business district - a growing financial and transport hub between the city centre and the recently opened Beijing Daxing International Airport, to the south, also designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. The new business district is integral to Beijing’s multimodal urban plan to accommodate growth without overburdening the centre. The tower delivers 172,800 sqm across 45 ellipsoid storeys. The building rises from a sunken courtyard. Its 5G powered spaces respond to demand from small and medium-sized businesses for flexible and efficient Grade A office space. Like all the other Soho China projects the task is to create a buzzing entrepreneurial hub gathering and networking hundreds of small businesses. However, the special challenge here is to create such a business communication hub within a tower, so far the only tall tower trying to deliver the Soho concept. The solution is provided by the idea of the mega-atrium.

The connectivity of the site is exceptional, adjacent to the business district’s rail station at the intersection of five new lines currently under construction on Beijing’s Subway network. Leeza SOHO’s site is diagonally dissected by an underground subway service tunnel. Straddling this tunnel, the tower’s design divides its volume into two halves enclosed by a single facade shell. The emerging space between these two halves extends the full height of the tower, creating the world’s tallest atrium at 194.15 m which rotates through the building as the tower rises to realign the upper floors with Lize road to the north. This rotation of the mega-atrium intertwines Leeza SOHO’s two halves in a dynamic ‘pas de deux’ with connecting sky bridges on levels 13, 24, 35 and 45; the glazed atrium façade giving panoramic views across the city and invites views from the outside in. The twisting surfaces of the atrium gives rhythm and dynamism to the space and also facilitates and varies the views up and down the atrium, revealing more than a straight wall would. The sky bridges serve as structural ties and punctuate the free flow of the space.

Leeza SOHO’s atrium acts as a public square for the new business district, visually linking all spaces within the tower and creating a new civic space for Beijing that is directly connected to the city’s transport network. The atrium also brings natural light deep into the building. The atrium is also acting as a thermal chimney with an integrated ventilation system that maintains positive pressure at low levels to limit air ingress and provides an effective clean air filtration process within the tower’s internal environment.

Fig.7 Zaha Hadid Architects, Leeza Soho Tower, Beijing 2019

The view from the neighboring urban spaces and towers into the communication void is as imporatant as the views across the void and the views from inside out. The void draws its audiences in and up the tower.

Fig.8 Zaha Hadid Architects, Leeza Soho Tower, Beijing 2019

The void reveals to each floor what goes on many more floors, above and below, inspiring interawareness as a first step to productive social interaction. It also provides awareness of the urban life beyond.

Fig.9 Zaha Hadid Architects, Leeza Soho Tower, Beijing 2019

This spiralling, pulsating void is the tallest atrium in the world, and probably one of the brightest. The dramatic verticality and transparency is reminiscent of the tallest Gothic spaces.

Fig.10 Zaha Hadid Architects, Leeza Soho Tower, Beijing 2019

The ellipsoid volume is cladded by full storey high shifting shingles that flatten out as the faced approaches the mega-window. This sophisticated parametric variation enhances the plasticity of the volume and gives, despite the use of only flat panes a very smooth, elegant expression.

As with our Macao project, it is important that the mega-atrium is not a hermetic space but also visually connects with the surrounding urban fabric. This reduces vertigo and enhances the sensation of freedom. Entering this space delivers a viscerally uplifting experience, reminiscent of the tallest Gothic cathedrals. This too is in architecture’s power.

End

Leeza Soho Tower Project Credits:

Architect: Zaha Hadid Architects

Design: Zaha Hadid & Patrik Schumacher

Project Director: Satoshi Ohashi

Project Architect Philipp Ostermaier

Project Associates: Kaloyan Erevinov, Ed Gaskin, Armando Solano

Project Team:

Yang Jingwen, Di Ding, Xuexin Duan, Samson Lee, Shu Hashimoto,

Christoph Klemmt, Juan Liu, Dennis Brezina, Rita Lee, Seungho Yeo,

Yuan Feng, Zheng Xu, Felix Amiss, Lida Zhang, Qi Cao

Competition Project Directors:

Satoshi Ohashi, Manuela Gatto

Competition Team Lead Designers:

Philipp Ostermaier, Dennis Brezina, Claudia Glas Dorner

Competition Team:

Yang Jingwen, Igor Pantic, Mu Ren, Konstantinos Mouratidis,

Nicholette Chan, Yung-Chieh Huang

Executive Architect: Beijing Institute of Architectural Design (China)

Consultants:

Structure: Bollinger + Grohmann (Stage 0,1),

China Academy of Building Research (Stage 2)

Beijing Institute of Architectural Design (Stage 3,4)

Façade: Konstruct West Partners (Stage 2)

Kighton Facade (Stage 3,4), Yuanda (Stage 3,4)

MEP: Parsons Brinkerhoff (Stage 2)

Beijing Institute of Architectural Design (Stage 3,4)